Che Guevara

Ernesto Guevara de la Serna (June 14, 1928Birthdate[›] – October 9, 1967), commonly known as Che Guevara or simply Che, was an Argentine-born physician best known for his leading role in the Cuban Revolution of the 1950s, his prominent roles in the Cuban revolutionary government, and for his subsequent resignation from his Cuban offices in order to devote himself to further attempts to spread Marxist revolution around the world.

Guevara's motorcycle tour of Latin America as a young man brought him into direct contact with the severe poverty that afflicts many people in the region, a sharp contrast to the well-off surroundings in which he had been raised. He moved to Guatemala, and his involvement in the leftist social revolution under Guatemala's first democratically-elected president, Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán, and his witnessing the 1954 right-wing military coup orchestrated by the American CIA radicalized Guevara; he became convinced that only a revolution by force against capitalism and against the influence of the United States in particular could remedy Latin America's extreme economic inequality. Guevara moved on to Mexico, where he met Raúl and Fidel Castro and joined the brothers' paramilitary 26th of July Movement to overthrow US-leaning General Fulgencio Batista. Though only 12 members survived the group's disastrous initial landing in Cuba, they finally overthrew Batista's government on January 1, 1959. Guevara served in various important posts in the new government, and wrote a number of articles and books on the theory and practice of guerrilla warfare. Very influential with Cuban leader Fidel Castro, Guevara advocated a hardline anti-capitalist foreign policy involving active efforts to create further socialist revolutions abroad and preparation for direct military conflict with the United States. He grew increasingly disillusioned with the Soviet Union, especially after the Soviets agreed to remove their long-range nuclear missiles from Cuba during the Cuban Missile Crisis, which he viewed as a betrayal. Guevara then went on several diplomatic missions to other Third World countries in an unsuccessful attempt to forge an anti-capitalist political and economic bloc that was not aligned with the Soviet Union.

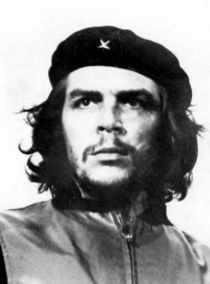

Guevara resigned his government posts and left Cuba in 1965 with the intention of directly fomenting Marxist revolutions abroad himself. He first went to the Congo-Kinshasa (later called the Democratic Republic of the Congo), and then to Bolivia. He did not meet with the widespread popular support he had expected in either country, and both operations were unsuccessful. He was captured in Bolivia by a CIA/ U.S. Army Special Forces-organized military operation and was executed shortly thereafter, in La Higuera near Vallegrande on October 9, 1967. Participants in, and witnesses to, the events of his final hours testify that his captors executed him without trial. After his death, Guevara became an icon of socialist revolutionary movements worldwide. An Alberto Korda photo of Guevara (shown) has received wide distribution and modification. The Maryland Institute College of Art called this picture "the most famous photograph in the world and a symbol of the 20th century."